Tassels

“You don’t want to go to the ceremony either.” Sharon’s

assertion, although listless, was meant to draw me away from the back door

before I stepped outside.

“I don’t, but Melanie wants us there,” I replied. “Your

sister thought the family would never see Felicia graduate.”

“Peter was supposed to graduate,” Sharon forlornly

replied.

An obligatory nod of acknowledgement was the only

response I was willing to give. It was pointless to do or say something that

wouldn’t alter Sharon’s mood. I made my exit, appreciative of the warmth and

brightness of a sunny, late spring afternoon. White clouds drifted across the

sky like irregularly shaped yachts transporting passengers who were unconcerned

about where they were going, when they got there or much of anything else. I

waited in the car, air ventilation system exhaling a cooled breeze, until

Sharon stepped outside a minute or two later. She wore cream-colored slacks and

a white blouse. She would have been in more festive pastel colors if Peter had

also been graduating. I backed the car out of the driveway, reminding myself to

avoid the route that would take us near the street where our son’s life ended.

A proposition had been on my mind for several days, and I considered presenting

it to Sharon before we reached the auditorium. There had been no hesitation

when I asked Sharon to marry me. I was young, athletic and sharp. I figured a

guy like me should be able to get a slightly taller and prettier than average

girl to accept my proposal. But I was uncertain about the proposition I had in

mind, so I chose to end the silence between Sharon and me with what I thought

would be a comforting assurance.

“There won’t be any mention of Peter during the

ceremony,” I announced. “I spoke with the principal. He said he would advise

everyone making a speech today to refrain from talking about what happened.”

“No mourning or recognition for Peter,” Sharon replied.

“You are still trying to ignore him.”

“No. I didn’t want you to feel like you were attending

another funeral for him.” I was louder and sterner than I meant to be. Sharon

had made me defensive.

“Every day is like a funeral.”

I didn’t respond to what Sharon said. There was no point

in commenting on the state our lives had been in for nearly two months. I

wanted to turn on the car stereo—have something other than the barely

noticeable sighing of the air ventilation—but Sharon probably would have

accused me of seeking to entertain myself instead of paying serious attention

to the memory of our son.

“Peter didn’t want to get in the car with that boy the

other times he was asked.” Sharon had previously made that statement on

numerous occasions, the first being when she shrieked it at the grim-faced

messenger in a cop’s uniform as he stood in our living room.

“Well, he finally did,” I commented. My hypothesis

regarding Peter’s decision to put himself in the passenger seat of the

nineteen-year-old’s car went unsaid. “That young man…he used to be one of

Peter’s classmates?” I asked, needing to talk about something other than why

Peter did what he did that evening.

“He graduated last year. He was in a couple of Peter’s

classes,” Sharon responded. “They would see each other when the two of them

were out and about. That boy kept trying to get Peter to go cruising with him,

but Peter usually refused. There was always an open beer can in the car’s

cupholder. Peter would tell the boy he wanted to keep walking and get more

exercise, that was his excuse for not accepting a ride…except that particular evening.”

“Peter told you those things?”

“Yes, because I listened to our son. I corrected

him when he was wrong, but not every conversation was a one-sided lecture or

criticism.”

Any conversational path would lead to a bad place, so I

focused my attention on navigating the roads leading to the auditorium. The

parking lot was nearly full when we arrived. Teenagers, dressed in forest green

gowns and square caps only geometry teachers could appreciate, strolled towards

the entrance with acquaintances of all ages. I didn’t want to be there, but

staying in the house where Peter was spurred to meet his end was not an

appealing option. I sighed and stepped out of the car. Sharon didn’t move until

I circled back to the car, opened the door on her side and took her by the

hand.

#

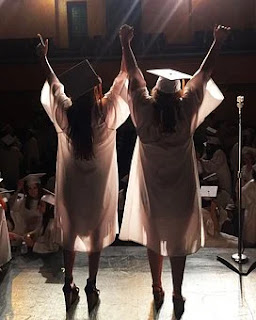

Nearly two and a half hours later the graduating class of

Maxwell Feldon High School rose in unison at the principal’s command,

undoubtedly the only time he was able to get a large group of students to do

his bidding without so much as a grumble of discontent. I turned to Sharon and

said, “The students that have gold tassels on their caps—”

“Are the honor students, I know,” Sharon said. “The

principal will tell all the students to move their tassels from the right side

of their caps to the left. That’s how it was when we graduated.”

I turned away from Sharon, my attempt at small talk

stymied. Sharon and I had been dating for over a year when we graduated, and at

the time I envisioned a future with her, a future of marriage and children. My

imaginings didn’t conceive a family of three which included an ungainly son

with a body that seemed to be made of pipestems, a science fiction nerd who

read and wrote poetry, of all things. A kid who listened to odd music on a

college radio station and frequently made references that were obscure to the

average, normal-thinking person.

The soon-to-be former students shifted their tassels in

the appropriate fashion as the principal instructed, the principal proclaimed

they had officially graduated and the auditorium roared with cheers and

applause. The proud onlookers stood, I for one glad to no longer be sitting in

a narrow, uncomfortable chair. I was also relieved that this would be the last

round of applause—the palms of my hands were stinging from clapping every time

someone said or did something everyone else in attendance deemed worth of

positive recognition. Graduates, faculty and various acquaintances flowed out

of the auditorium like plankton and silt being carried through numerous

channels by slow-moving streams.

A pretty young woman with shoulder-length hair halted her

stride at the sight of an older couple. “Daddy, Mom, I got it!” She waved her

diploma in the air as she called to the couple, her words truncated and warped.

Father and mother replied with frenetic hand gestures as their daughter bounded

towards them. Deaf girl. That was why the principal motioned for her to come

onstage and get her diploma—she couldn’t hear her name being called or the

applause meant for her. I turned away from the embracing trio, wanting to

locate Melanie and Felicia so I could congratulate Felicia, get in my

air-conditioned car and leave. Sharon wasn’t even trying to find her sister and

niece, just stayed still in her fog of melancholy.

“Mr. and Mrs. Hearns. Hello.” The timorous voice belonged

to a tiny, white-haired woman. The smile on her face partially masked the

unending weariness of trying to impart knowledge to someone else’s brats school

year after school year. “I’m Miss Traynor. I was Peter’s American Literature

teacher.”

“Miss Traynor,” Sharon flatly responded. I hadn’t

remembered the woman’s name, just recalled being unimpressed with what she’d

told us about Peter’s work and her teaching philosophy.

“Having Peter in my class was a delight,” Miss Traynor said.

“He wrote a poem for a classmate who was down in the dumps because of various

situations with which she was dealing. Her spirits were lifted when she read

that poem. She was giddy.”

Sharon managed to muster a smile for Miss Traynor. “He

did love writing poetry.”

“He also—”

“Aunt Sharon, Uncle William!” Felicia didn’t care that

her shouting interrupted a conversation. She and Melanie—her mother—headed our

way. Melanie, an older and slightly heavier version of her daughter, was

struggling to keep up with Felicia.

Miss Traynor gently touched our hands. “It was nice

seeing you again. Take care.”

Felicia stepped into the space vacated by Miss Traynor

and embraced Sharon, strands of her gold tassel brushing Sharon’s cheek and

chin. “Congratulations, honey.” There was very little joy in Sharon’s voice. I

gave my congratulations when Felicia hugged me, grateful that Felicia no longer

had the scent of a particularly acrid perfume she used to wear. A long gown,

tastefully thin layer of makeup, lipstick that was not a garish shade of

red…these were improvements over the short skirts, tight jeans, thick layers of

makeup and fuchsia lipstick on Felicia’s mouth that were intended to allure

half the boys in school—and gave her mother fits of anxiety.

Melanie pointed at Felicia. “Here is my high school

graduate.” She’d managed to raise a daughter after what’s-his-name walked out

on her and Felicia.

“Whooo, girl!”

“Fe-leeee-sha!”

Felicia waved in the direction of the shouting female

voices, broad smile below the round cheekbones of her pretty face. Felicia

started looking this way and that. “Miss Braun promised she’d be here.”

“You used to want to avoid her like the plague,” Melanie

remarked.

“Yeah, because she’s so demanding in class. I’d go to

dance class and get that treatment from her, then come home and have you

sitting at my desk in my room while I did my homework.”

“Yes,” Melanie replied. “I was in your sacred sanctuary

to make sure you did your homework and did it correctly—as best as I could

tell. I enrolled you in the dance school because you needed to do something

other than hang out with your friends, and when you were home you were always

bopping around the house with music coming through your earbuds so I figured

you might as well learn how to be entertaining with it.”

“I’ve had a lot of fun,” Felicia admitted.

“That’s one good result of it,” Melanie responded.

“We should leave so the two of you can look for Miss

Braun,” Sharon said to her sister and niece. This was probably Sharon’s way of

excusing herself from a scene that was too joyous, a scene which was supposed

to have included Peter.

“Thank you for being here,” Melanie responded as Felicia

waved and smiled at Sharon and me. “I’ll call you later.”

“From the back of the classroom to a seat at graduation!”

a brown-skinned man with male pattern baldness exclaimed. He shook the hand of

the grinning, muscular graduate who approached him.

“Science became interesting. I learned how some things

work.”

“Are you going to become a scientist?”

The graduate shook his head. “No. Gonna go to vocational

school.”

“Well, alright!”

Sharon and I weaved around mechanical and human obstacles

in the parking lot.

We would soon be back home,

the location of the beginning of Peter’s end. A place where I didn’t want to

be, but maybe it would become a place of newfound hope after I gave my

proposition to Sharon. I waited until the auditorium was no longer visible

through the side window, then made my pitch to Sharon. “Adoption,” I said,

wishing I could have come up with a better way to introduce my idea. Peter had

been quite the wordsmith. He probably would have been capable of doing so.

“What?”

“If we’re able to adopt in the next couple of years we

won’t be very old by the time the child graduates from high school.”

There was a brief silence before Sharon spoke. “And if

something goes wrong, do we also replace him like pet owners replacing a

guppy?” Her voice rose to an earsplitting shriek.

My suggestion was not going to begin a healing process

for Sharon and me, and I resigned myself to the belief that nothing would. The

remainder of the journey home was mercifully brief. Sharon abandoned her copy

of the graduation program on the front passenger seat and headed for our

bedroom to commence a session of weeping. I took to the den and collapsed in my

recliner. It was nearly two months ago when I strolled into that room with a

bottle of beer and found Peter on the couch, eyes fixated on his laptop’s

screen, one of his science fiction fan magazines on the coffee table. My son,

gawky and pimple-faced and sometimes in need of tutoring for his Algebra II

class. I had sighed and shook my head in disgust. Peter rose from the couch

after I sat in my recliner. Peter exited the den and I didn’t care where he

chose to go.

Peter went for a walk, and that evening he accepted a

ride from the friend who was too intoxicated to operate his car.

I leaned back in the recliner and started my own crying

session, wishing I could use the time machine in one of Peter’s magazines to do

some things differently…and undo what I shouldn’t have done.

Dell R. Lipsco

Dell R. Lipsco’s short fiction has appeared in several publications including Adelaide, Conceit Magazine, Across the Margin and Timbooktu. His story "Rough Edges" was included in Potato Soup Journal's "Best of 2020" anthology. He resides in the Blue Ridge Region of Virginia.

refreshing and inventive. give us more.

ReplyDeleteThank you for the positive feedback. I am currently working on other projects that I intend to share in the near future. Yours Truly, Dell R. Lipscomb

Delete